Threads (in Ruby): Enough Already

For a while now, the Ruby community has become enamored in the latest new hotness, evented programming and Node.js. It's gone so far that I've heard a number of prominent Rubyists saying that JavaScript and Node.js are the only sane way to handle a number of concurrent users.

I should start by saying that I personally love writing evented JavaScript in the browser, and have been giving talks (for years) about using evented JavaScript to sanely organize client-side code. I think that for the browser environment, events are where it's at. Further, I don't have any major problem with Node.js or other ways of writing server-side evented code. For instance, if I needed to write a chat server, I would almost certainly write it using Node.js or EventMachine.

However, I'm pretty tired of hearing that threads (and especially Ruby threads) are completely useless, and if you don't use evented code, you may as well be using a single process per concurrent user. To be fair, this has somewhat been the party line of the Rails team years ago, but Rails has been threadsafe since Rails 2.2, and Rails users have been taking advantage of it for some time.

Before I start, I should be clear that this post is talking about requests that spent a non-tiny amount of their time utilizing the CPU (normal web requests), even if they do spend a fair amount of time in blocking operations (disk IO, database). I am decidedly not talking about situations, like chat servers where requests sit idle for huge amounts of time with tiny amounts of intermittent CPU usage.

Threads and IO Blocking

I've heard a common misperception that Ruby inherently "blocks" when doing disk IO or making database queries. In reality, Ruby switches to another thread whenever it needs to block for IO. In other words, if a thread needs to wait, but isn't using any CPU, Ruby's built-in methods allow another waiting thread to use the CPU while the original thread waits.

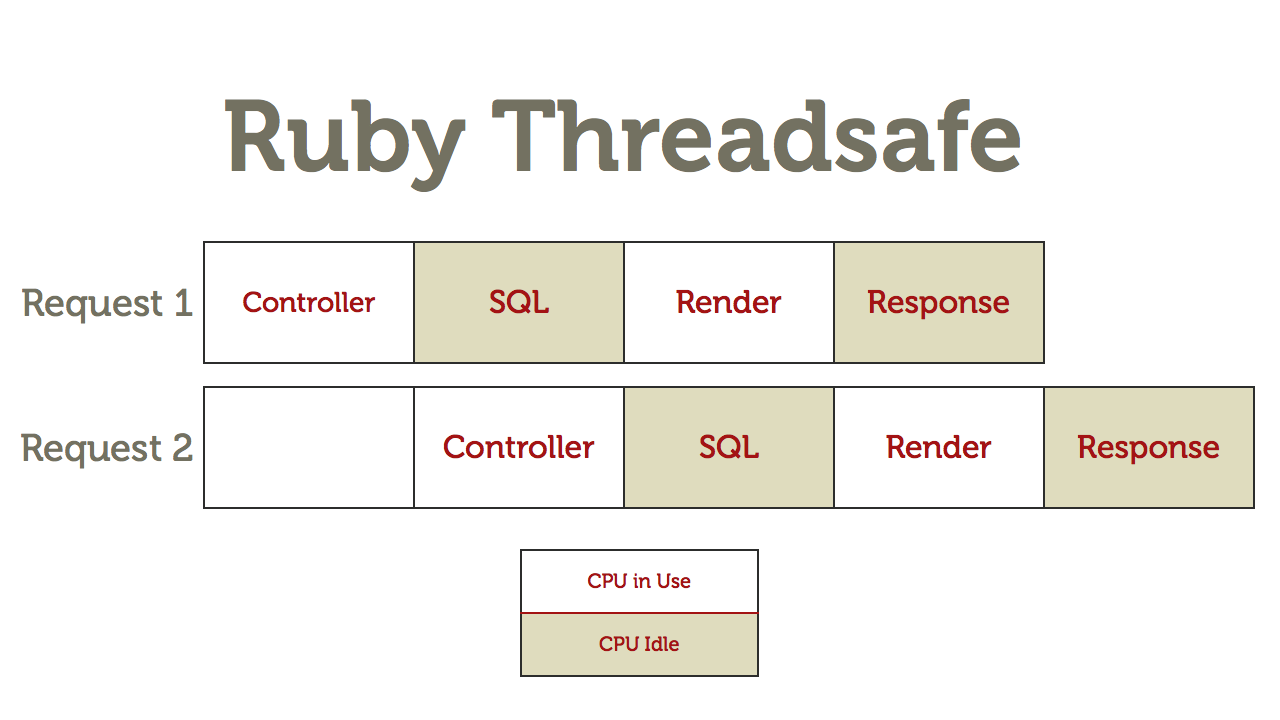

If every one of your web requests uses the CPU for 30% of the time, and waits for IO for the rest of the time, you should be able to serve three requests in parallel, coming close to maxing out your CPU.

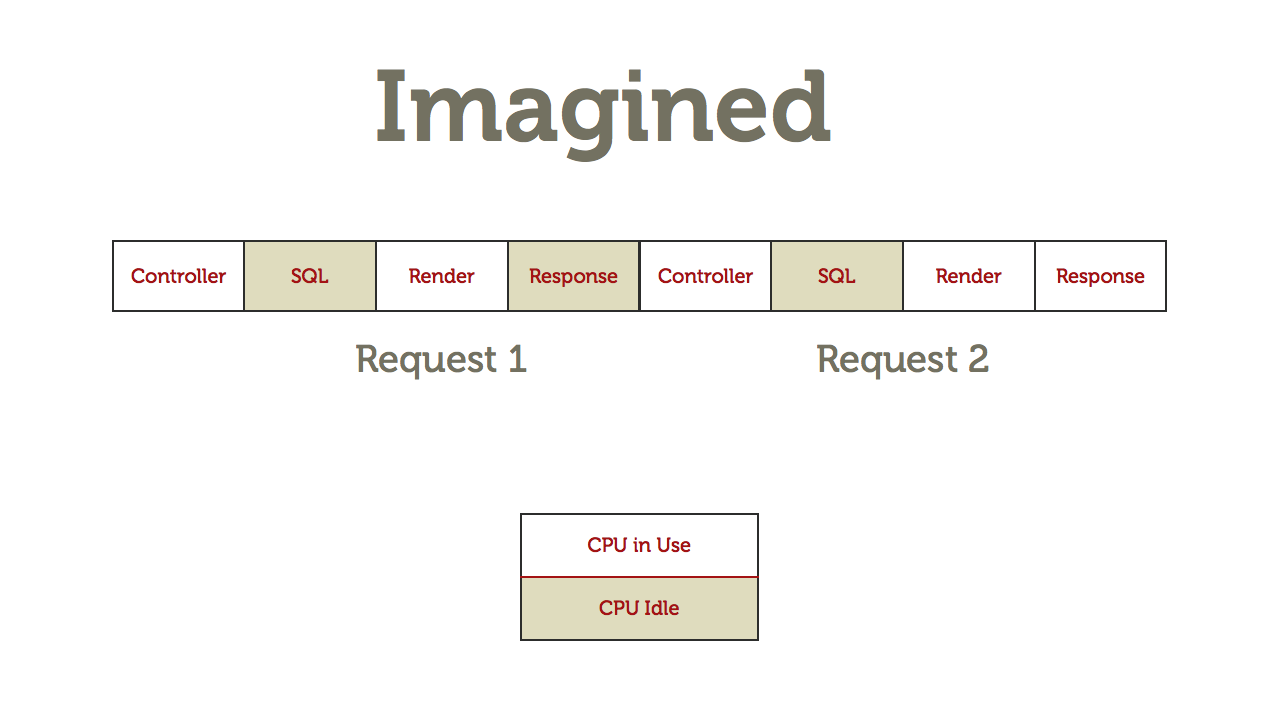

Here's a couple of diagrams. The first shows how people imagine requests work in Ruby, even in threadsafe mode. The second is how an optimal Ruby environment will actually operate. This example is extremely simplified, showing only a few parts of the request, and assuming equal time spent in areas that are not necessarily equal.

I should be clear that Ruby 1.8 spends too much time context-switching between its green threads. However, if you're not switching between threads extremely often, even Ruby 1.8's overhead will amount to a small fraction of the total time needed to serve a request. A lot of the threading benchmarks you'll see are testing pathological cases involve huge amounts of threads, not very similar to the profile of a web server.

(if you're thinking that there are caveats to my "optimal Ruby environment", keep reading)

"Threads are just HARD"

Another common gripe that pushes people to evented programming is that working with threads is just too hard. Working hard to avoid sharing state and using locks where necessary is just too tricky for the average web developer, the argument goes.

I agree with this argument in the general case. Web development, on the other hand, has an extremely clean concurrency primitive: the request. In a threadsafe Rails application, the framework manages threads and uses an environment hash (one per request) to store state. When you work inside a Rails controller, you're working inside an object that is inherently unshared. When you instantiate a new instance of an ActiveRecord model inside the controller, it is rooted to that controller, and is therefore not used between live threads.

It is, of course, possible to use global state, but the vast majority of normal, day-to-day Rails programming (and for that matter, programming in any web framework in any language with a request model) is inherently threadsafe. This means that Ruby will transparently handle switching back and forth between active requests when you do something blocking (file, database, or memcache access, for instance), and you don't need to personally manage the problems the arise when doing concurrent programming.

This is significantly less true about applications, like chat servers, that keep open a huge number of requests. In those cases, a lot of the application logic happens outside the individual request, so you need to personally manage shared state.

Historical Ruby Issues

What I've been talking about so far is how stock Ruby ought to operate. Unfortunately, a group of things have historically conspired to make Ruby's concurrency story look much worse than it actually ought to be.

Most obviously, early versions of Rails were not threadsafe. As a result, all Rails users were operating with a mutex around the entire request, forcing Rails to behave like the first "Imagined" diagram above. Annoyingly, Mongrel, the most common Ruby web server for a few years, hardcoded this mutex into its Rails handler. As a result, if you spun up Rails in "threadsafe" mode a year ago using Mongrel, you would have gotten exactly zero concurrency. Also, even in threadsafe mode (when not using the built-in Rails support) Mongrel spins up a new thread for every request, not exactly optimal.

Second, the most common database driver, mysql is a very poorly behaved C extension. While built-in I/O (file or pipe access) correctly alerts Ruby to switch to another thread when it hits a blocking region, other C extensions don't always do so. For safety, Ruby does not allow a context switch while in C code unless the C code explicitly tells the VM that it's ok to do so.

All of the Data Objects drivers, which we built for DataMapper, correctly cause a context switch when entering a blocking area of their C code. The mysqlplus gem, released in March 2009, was designed to be a drop-in replacement for the mysql gem, but fix this problem. The new mysql2 gem, written by Brian Lopez, is a drop-in replacement for the old gem, also correctly handles encodings in Ruby 1.9, and is the new default MySQL driver in Rails.

Because Rails shipped with the (broken) mysql gem by default, even people running on working web servers (i.e. not mongrel) in threadsafe mode would have seen a large amount of their potential concurrency eaten away because their database driver wasn't alerting Ruby that concurrent operation was possible. With mysql2 as the default, people should see real gains on threadsafe Rails applications.

A lot of people talk about the GIL (global interpreter lock) in Ruby 1.9 as a death knell for concurrency. For the uninitiated, the GIL disallows multiple CPU cores from running Ruby code simultaneously. That does mean that you'll need one Ruby process (or thereabouts) per CPU core, but it also means that if your multithreaded code is running correctly, you should need only one process per CPU core. I've heard tales of six or more processes per core. Since it's possible to fully utilize a CPU with a single process (even in Ruby 1.8), these applications could get a 4-6x improvement in RAM usage (depending on context-switching overhead) by switching to threadsafe mode and using modern drivers for blocking operations.

JRuby, Ruby 1.9 and Rubinius, and the Future

Finally, JRuby already runs without a global interpreter lock, allowing your code to run in true parallel, and to fully utilize all available CPUs with a single JRuby process. A future version of Rubinius will likely ship without a GIL (the work has already begun), also opening the door to utilizing all CPUs with a single Ruby process.

And all modern Ruby VMs that run Rails (Ruby 1.9's YARV, Rubinius, and JRuby) use native threads, eliminating the annoying tax that you need to pay for using threads in Ruby 1.8. Again, though, since that tax is small relative to the time for your requests, you'd likely see a non-trivial improvement in latency in applications that spend time in the database layer.

To be honest, a big part of the reason for the poor practical concurrency story in Ruby has been that the Rails project didn't take it seriously, which it difficult to get traction for efforts to fix a part of the problem (like the mysql driver).

We took concurrency very seriously in the Merb project, leading to the development of proper database drivers for DataMapper (Merb's ORM), and a top-to-bottom understanding of parts of the stack that could run in parallel (even on Ruby 1.8), but which weren't. Rails 3 doesn't bring anything new to the threadsafety of Rails itself (Rails 2.3 was threadsafe too), but by making the mysql2 driver the default, we have eliminated a large barrier to Rails applications performing well in threadsafe mode without any additional research.

UPDATE: It's worth pointing to Charlie Nutter's 2008 threadsafety post, where he talked about how he expected threadsafe Rails would impact the landscape. Unfortunately, the blocking MySQL driver held back some of the promise of the improvement for the vast majority of Rails users.